More than 4,000 preventable mistakes occur in surgery every year at a cost of more than $1.3 billion in medical malpractice payouts, according a new study.

How preventable? Well, researchers call them “never events” because they are the kind of surgical mistakes that should never happen, like performing the wrong procedure or leaving a sponge inside a patient’s body after surgery.

But researchers found that paid malpractice settlements and judgments for these types of never events occurred about 10,000 times in the U.S. between 1990 and 2010. Their analysis estimates that each week surgeons:

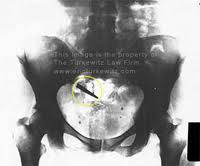

- Leave a foreign object like a sponge or towel inside a patient’s body after an operation 39 times

- Perform the wrong procedure on a patient 20 times

- Operate on the wrong body site 20 times

“I continue to find the frequency of these events alarming and disturbing,” says Donald Fry, MD, executive vice president at Michael Pine and Associates, a health care think tank in Chicago. “I think it’s a difficult thing for clinicians to talk about, but it is something that must be improved.”

Surgical Mishaps Happen

In the study, researchers looked at malpractice claim information for surgical never events from the National Practitioner Data Bank from 1990 to 2010. The results are published in Surgery.

Malpractice settlements and judgments relating to leaving a sponge or other object inside a patient, performing the wrong operation, operating on the wrong site or on the wrong person were included in their analysis.

The results showed a total of 9,744 paid malpractice judgments and claims for these types of never events were reported over the 20-year period, totaling $1.3 billion.

Based on these results, researchers estimate that 4,044 surgical never events occur each year in the U.S.

Researchers say the actual number of these surgical mistakes is likely even higher.

“What we report is the low end of the range because many never events go unreported,” says researcher Marty Makary, MD, MPH, associate professor of surgery at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

Makary says by law, hospitals are required to report never events that result in a settlement or judgment.

But not all items left behind after surgery are discovered. They are typically only reported when a patient experiences a complication after surgery, and doctors try to find out why.

“We believe the events we describe are real,” says Makary. “I cannot imagine a hospital paying out a settlement for a false claim of a retained sponge.”

The consequences of surgical mistakes ranged from temporary injury in 59% of the cases to death in 6.6% of the cases and permanent injury in 33% of people affected.

When Mistakes Occur

The study showed surgical mistakes happened most often to people between the ages of 40 and 49. Surgeons in this same age group were also accountable for more than a third of the never events compared with 14% for older surgeons over age 60.

“Surgeons involved in retained sponges tended to be in the middle part of their career, dispelling the idea that surgeons at the beginning or end of their careers have most of these events,” says Makary.

Nearly two-thirds of surgeons involved in a surgical mistake had been cited in more than one separate malpractice report in the past, and 12.4% were named in more than one surgical never event.

How to Prevent Surgical Mistakes

Researchers say most medical centers have long had patient safety procedures in place to prevent surgical mistakes, such as mandatory “time-outs” in the operating room to make sure medical records and surgical plans match the patient on the table.

In addition, counting sponges and other equipment before and after surgery, using surgical checklists, and indelible ink to mark the site of the surgery are also common safety procedures.

Fry says even with these precautions in place, mistakes still happen.

“Even with marking the surgical site there are reports of the wrong site still being operated on, and you have to say it’s a lack of attention to detail when it happens,” he says.

Makary says new technology, like surgical sponges with radiofrequency tags that can be detected by a scanner, should help reduce the number of common surgical mistakes as they are adopted.

In addition to adopting new technologies to increase patient safety, Makary says a new standardized system of reporting surgical mistakes is needed to properly measure and address the problem

Finally, Makary and Fry say greater attention should be paid to the culture of safety and teamwork among nurses, surgeons, and everyone else in the operating room.

Meanwhile, Fry says it’s not out of line to speak up and discuss safety concerns with your surgeon prior to surgery.

“I do think it’s always appropriate for concerned patients to discuss the issues about what will be done to make sure that this doesn’t happen to me or my family member,” says Fry.